In Living Color:

Writing About Love, Loss, and the Beauty of Motherhood

by Julie Buxbaum

Both of my children came into the world with a certain measure of theatrics. My daughter was born yellow. Not mildly yellow, mind you, which arguably could have been a genetic quirk, but no, she was a florescent yellow, her eyes rheumy and glow in the dark. My son arrived three years later with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck. He had decided to be a different primary color. Blue. The color of a bruise. I should stop now and make clear that I am crazy lucky. Both of my kids, despite their early and continued flair for the dramatic, turned out to be 100 percent fine. And so their entrances into the world have always felt a bit metaphorical to me. The necessary first punch in the gut of adulthood.

The thing is, for a long time before I had kids, I was in denial about the fact that I was a grown-up. My mom died when I was 14, and so she wasn’t around to help me master the many pseudo-markers of maturity. (I’m a terrible cook. I’m hopeless at cleaning. It’s a miracle that my taxes get filed on time or at all.) But when my own children came into the world in screaming techno-color, I had no choice but to ignore the quiet, terrified voice that said this isn’t what I signed up for, and instead to listen to the louder, more insistent one which had already realized this is exactly what I signed up for. The one that said: Welcome to motherhood.

I was officially an adult.

This shouldn’t have been such a revelation. In addition to being a mother, I am also a homeowner, a novelist, a wife, and I’m quickly nearing the big 4-0. But saying this sentence out loud — I am an adult — somehow feels like an uncomfortable acknowledgement of how long my own mother has been gone. (24 years. How is that even possible?) Even more painful is the realization that I am no longer the person my mom once knew. In fact, I’m now someone she wouldn’t even recognize.

So I sometimes wonder if my mother ever daydreamed about this future incarnation of me. Did she like to think that I’d one day drink bad coffee at PTA meetings and steal into my kids’ bedroom at night to check that they were still breathing just like she used to? Did she expect me to grow into the kind of mom who keeps Cheerios and baby wipes and extra toddler underwear in her purse? And maybe this most of all: When she got sick, did my mom ever allow herself to think about how much and how often this new grown-up me would wish she were here to guide me? How perverse it is that I so badly want to ask her how I should talk to my kids about her death, ask her how I am supposed to explain to them what still feels unexplainable to me even 24 whole years later?

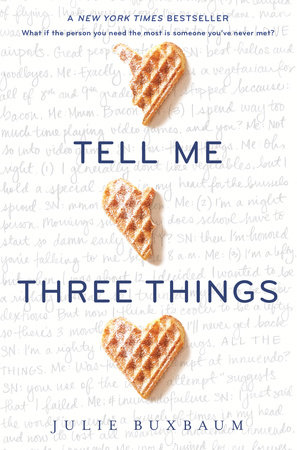

When I sat down to write my first YA novel Tell Me Three Things, I didn’t intend for it to be a therapeutic exercise. Somehow, though, (and I blame the post-natal sleep deprivation) I found myself getting deeply personal and I unwittingly created a girl named Jessie who had also lost her mom at fourteen. On the page, I began to revisit a period in my life I had long ago decided just not to think about. Until recently, it was too painful to remember those teenage years full of searing loss and grief.

At one point in the book, Jessie says of her mother, “she will never see who I grow up to be — that great mystery of who I am and who I am meant to be — finally asked and answered.” And it is true my mother did not get to see who I grew up to be or to read the book that was created from the legacy of losing her. But I am so grateful that having my own kids finally gave me the courage to write Tell Me Three Things, to revisit teenage me in my writing, and to say goodbye to that delicate version of myself, once and for all. Now, in the full bloom of adulthood, I imagine the people my children will one day grow up to be, as I tell myself my mother once did for me. I imagine that the story of their births will transform from the metaphorical into a prophecy. I close my eyes and picture them one day painting our world full of color.