Why Children’s Books About Black Joy Are So Important

by Katheryn Russell-Brown

My Love of Books

My childhood was filled with books. They brought me so much joy. There were so many books to fall in love with. In 2nd grade, I read Ramona and Beezus by Beverly Cleary. I didn’t know anyone like Ramona, who was so funny and sure of herself. When I read E. B. White’s Stuart Little in third grade, I remember being worried about him — a mouse! — and hoping he was safe from harm. In 5th grade, when I read Jamesand the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl, I wanted to lift off the ground and glide across the sky in a hot-air balloon, just like James. After reading Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh, I fancied myself as a community detective — walking the streets and scribbling in my notebook — chronicling everyone’s comings and goings.

My favorite teacher was Mrs. Riles, who taught sixth grade. Our classroom had a big, overstuffed chair you could sink into and read. Mrs. Riles validated my book love by encouraging all of us to read. She offered all sorts of incentives, including a prize for reading the most books (I won!).

Missing Black Children

It wasn’t until I was a young adult that it hit me: When I was in grade school, I hardly ever saw or read any books with Black characters. Ezra Jack Keats’s books, including Peter’s Chair, Whistle for Willie, and The Snowy Day, are among the few books that come to mind. I loved these books, with characters who had the same skin color as me, who played outside, loved pets, and didn’t want to get into trouble with their parents. These books were fantastic, but they were outliers.

In the big sea of books I read as a child, where was I — a skinny, brown-skinned, flat-chested Black girl?

It wasn’t until junior high that I was assigned books with Black characters. I vividly remember Louise Meriwether’s book, Daddy Was a Number Runner, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Alex Haley’s searing biography.

The bottom line is that I read very few books with Black main characters during my formative years.[1]That amounts to years of not seeing my reflection on the hundreds of pages I was turning. As Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop says, books can be mirrors, windows, or sliding doors. In my case, the books I’d read weren’t reflections of my life, nor were they stories inviting me to join in. I needed books to be mirrors, windows, and sliding doors. All I had were windows.

Fast Forward

Today, lots of books feature Black children. I wish, however, that more of these books fit into the “Black joy” category or what I would describe as stories about everyday Black children navigating today’s world. These tales should be the norm. There should be twice as many books featuring Black children having routine childhood experiences as there are children’s books about slavery, segregation, and overcoming discrimination.

The children’s books I’ve written are stories of Black girls and women who overcame obstacles and fought for fair treatment. My first book, Little Melba and Her Big Trombone, tells the story of a young girl who loved the trombone — a large instrument that few girls played. She was dedicated to her horn, even when people discouraged her. She played with delight.

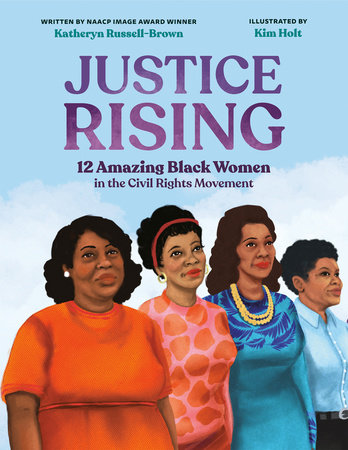

My newest book is Justice Rising: 12 Amazing Black Women in the Civil Rights Movement. This book tells the story of twelve Black women and girls who contributed to making a better world for us all. Some of them led marches, taught school, organized protests, sang, and wrote letters.

Books featuring Black children should reflect the world. Stories of racial protest and overcoming discrimination should exist beside stories of Black children playing on swings, daydreaming in class, and learning to potty train a new pet.

[1] I found out later that there were many children’s books with Black characters. For instance, books by Lucille Clifton, Leo and Diane Dillon. Notably, books with Black characters represented a tiny slice of the overall children’s book market.

-

Books by the Author: