How the Urgency of Motherhood Made Me a Writer

by Rachel Starnes

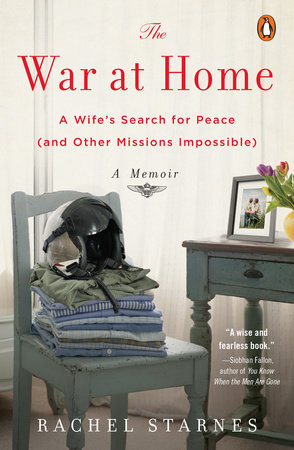

I have been married to a U.S. Navy fighter pilot for nearly 12 years. The recent publication of my first book, a memoir of our marriage and journey into parenthood, with its attendant echoes into some of the more painful parts of my own childhood, has afforded me the opportunity to reflect on the role of writing in my life, what my work is, and what it means to have “my own thing.”

These days I am a stay-at-home mom to our boys, ages four and six. I write in the two hours my youngest is at preschool, during his naps, and late at night, but the lion’s share of my time and energy goes to laundry, meals, housework, and mothering. If we are what we do most, then I am a mother and wife primarily, and, on occasion, a writer. This was not how I envisioned my adulthood, or the unfolding of my working identity, as a child.

My dad worked on offshore oil rigs, which meant he did rotational work which took him away from home for stretches that varied from two weeks to several months. Missing him was a huge part of my emotional landscape. So was witnessing the strains his absence put on my mom — her loneliness, her frustrations, her fears, and what I perceived to be her limited options, despite her being a talented actress. My childhood plan for a fearless, feminist adulthood was to achieve financial independence in a passion-fueled, adventurous career first, and then maybe get married.

But life had other plans, and when I found Ross, the person I wanted to spend it with, and he wanted desperately to be a fighter pilot, I had to reassess. I had only just barely checked off financial independence, having recently conceded that my passion, writing, might always be separate from my paying work. This concession stung all the more when a friend of my soon-to-be husband once lost patience with my description of the multifaceted university administration work I did and said that if I couldn’t describe what I was in one word, then I didn’t know. “Doctor,” he said pointing to himself, a first year resident, and then, “Pilot,” pointing to Ross, not yet in training. I said nothing. I lacked their clarity of vision, their audacity.

Life as a Navy wife taught me volumes. I became good at reinventing home in new places — seven homes in four states will do that. I worked in bookstores and taught community college writing labs, but my work was always temporary and disjointed. I wrote steadily, but what I wrote lacked focus. Finally, I found a job that allowed me to complete an MFA, but by that time we were six years into our marriage and I had also found that I wanted to have children. I was just finishing my degree when we decided to start a family, and we agreed that it made the best financial sense for me to stay home, at least for a few years. My work finally had a single word: Mother.

And yet, raising babies was when I doubled down on writing. I wrote with urgency, in 15-minute bursts on a permanently open laptop on the high kitchen bar, and I wrote about my own life because it felt like the story of it was getting on top of me. Too much felt like repetition from my past, and I had to figure out how and why I had chosen this, and what, if anything, I was doing differently. Composing paragraphs in my head while I changed diapers and sketching out a structure for chapters on scrap paper as I pushed a grocery cart, I found that being two things at once suited and inspired me. I found a lifeline in those harried paragraphs, and a path toward creating something different, but I also found that I wasn’t lost. I needed my husband and my children as much as they needed me. Caring for them inspired me, but it also provided structure, scarcity, and a desire for a meaningful way to use what free time and talent I had.

Part of that discovery, and the process of publishing a book, has involved defining what writing is and isn’t to me. Writing isn’t: where I pour most of my time and energy; the first or only way I define myself; an escape plan in case my marriage fails; or the life I would rather be living. Writing is: a means of strengthening my critical thinking while also demanding my emotional authenticity and presence; a practice that can bend and flex around the needs of the care-work I do for my family; an outlet in which to pursue excellence; and a means of connecting with others in conversations that are meaningful to me.

My writing is my gift to my children and my husband because it frees them from the pressure of feeling that their lives, their successes or failures, are somehow beholden to me. And they can see me as an individual, succeeding and failing at something entirely on my own merit. I consider it an act of deep love and respect to be able to separate from them in this way, and to free them from myself.

Finally, it’s become a way of thinking that has helped me name the three things, not just one, that I’ve grown up to be and the circular way in which they surround and strengthen me: Wife, Mother, Writer.