Adam Gidwitz on the Magic of Telling Stories to Your Child

by Adam Gidwitz

My daughter used to have a phobia of fire alarms.

It probably started when she was an infant. We’d just moved into a new home, and near the kitchen, we had a very sensitive smoke detector connected to an insanely loud, house-wide fire alarm system. We tripped it quite a few times because one’s imperfections as a parent — no matter how fervently one tries to avoid them — are as unpredictable as they are innumerable.

For the first year of her life, fire alarms upset our daughter. I had to go to her daycare and sit with her as she cried one day after some routine fire alarm maintenance. And when a fire alarm went off at my in-laws’ house during her first holidays there, we could only get her to lie down in her bed again by rigging a complicated system of blankets to hide the smoke detector. (Somewhere, a fire marshal is screaming.)

Since covering every smoke detector in one’s home is neither practical nor safe, and since I can’t just show up at her daycare or preschool for every fire drill, we needed a better solution. What I began to do, because it is what comes most naturally to me, is to tell my daughter stories — true stories about her experiences with the fire alarm. I began with our experience at my in-laws’.

“We were all in the Berkshires. Nonni, Grandad, and Ellie were there. Suddenly, we heard a ‘Chirp chirp! Chirp chirp!’ noise. A smoke detector had a low battery! But which one? We checked every smoke detector in the house. We checked in the living room. But the smoke detector had a green light! All good! We checked…” The story ends with Grandad changing the battery in one smoke detector and setting off the whole fire alarm system. And what did my daughter do then? She hugged Nonni.

The first time I told her the story, she listened with eyes as wide as two smoke detectors. And when it ended, she immediately said, “Again!”

(One pro tip about telling stories to children — and anyone — is to trust your audience. If they want more, give them more. If they don’t seem to want more, tell a better story.)

So I told it again. As soon as it concluded, instantly, my daughter said, “Again!”

My wife worried that I was re-traumatizing our daughter by telling her about the experience over and over again. But as a writer of books for young people, I believe that children know what they need. If they want to hear the same story or read the same novel, over and over again, it is because there is something in that story that they need to process, master, and use in their emotional or intellectual growth.

Over the next many months, I told that story hundreds of times. And some magical things started to happen.

The first magical effect of this storytelling was my daughter’s language development. She had been barely verbal when we began. But within a few weeks, she was telling the story with me.

“We were all in the…”

“Behbeh.”

“That’s right, the Berkshires. Who was there?”

“Nonni!”

“Nonni was there. Who else was there?”

“Dada!”

“Right. Daddy was there. Who else was there?”

“Mama.”

“Mama was there. Suddenly, what did we hear?”

“Chirp chirp!”

“That’s right!”

And the story always ended with, “The fire alarm was so loud. And what did you do?”

“Ugged Nonni.” And she gave the sweetest sigh.

It was unbearably adorable. I have about 7,000 videos of that experience, but I don’t need them. I remember every last detail.

The next magical effect of this storytelling was the arrival of her imaginary friend. It happened the first time we recorded the story on camera.

“Who was there?”

“Nonni.”

“Nonni was there. Who else?”

“Mama.”

“Mama was there. Who else?

“Momo…”

“What? Who’s Momo?”

She started to giggle.

“Who is Momo?”

I started to laugh, too, and tickled her as I asked, “Who’s Momo?” My daughter broke out in hysterics. Those moments — of us laughing together over something funny she said in a story — are some of the best moments in my life. Yet another magic effect.

Forever after, Momo was a part of the story. And many stories to come. Momo accompanied my daughter on family trips and did scary things before my daughter did them. Momo and my daughter were inseparable until my daughter didn’t need her anymore. Then Momo faded away to the land of Beekle (as imagined by Dan Santat), Ted (as imagined by Tony DiTerlizzi), and Neverland (as imagined by J.M. Barrie in the most classic imaginary friend story).

We also talked to the fire alarms all the time. “Hello, fire alarm!” my daughter would say as we passed under one. “Fire alarms don’t go off when you dance under them. Right, fire alarm?” “Right!” the fire alarm would answer in my voice.

Soon, my daughter’s phobia of fire alarms subsided. Perhaps it would have anyway, with her natural development. But it certainly seemed like our storytelling played an important role.

To anyone who makes a living studying either children or stories, this will come as no surprise. Storytelling is humanity’s oldest art for a reason. It’s how we process our experiences, connect, learn from the past, and predict the future.

All humans crave stories, but children crave them with a unique ferocity. These days, many parents give their children the stories they crave through screens because we’re tired and have to get dinner on the table, do the laundry, call the credit card company, and so on. The iPad tells so many stories, so effortlessly. But stories were meant to be passed from human to human, and when a story comes from someone we love, we enjoy it all the more. And the storyteller, too. It is an act of alchemy. Of magic.

I encourage all parents to capture this magic. You can! Trust me! You don’t have to be a pro. You don’t have to make anything up. And you don’t have to buy a thing. Here are few tips for telling your kids stories:

Tell them the truth. Kids crave the truth. They love fiction, of course, but even the fictional stories you invent can center on an experience the children have had. My daughter and I created a great story about a dinosaur who throws up a lot. She had a nasty stomach bug, and she wanted to investigate her experience — thoroughly.

This brings me to my next tip: Tell them the story as often as they ask (without losing your sanity, of course). As I said, children know what they need — except when it comes to sugar. Somehow sugar short-circuits that whole survival instinct.

Moving on.

Next tip: For young children (under five), use repetitive language and sound effects. If you can find moments when they know it’s their turn to chime in, all the better. And build suspense, if you can. The more dynamic the story is, the more engaged they’ll be. (But don’t stress about this one; a simple story is far better than no story at all).

Finally, follow their lead. Kids often have the best ideas (like Momo). They know what they need.

Stories don’t cost a dime, and you don’t need a referral to get one. You don’t need to recharge them. You don’t have to snatch them back to navigate to your in-laws’. They don’t have product placements, nor do they hawk cheap consumer products. Stories are ancient, wholesome, and magical.

—

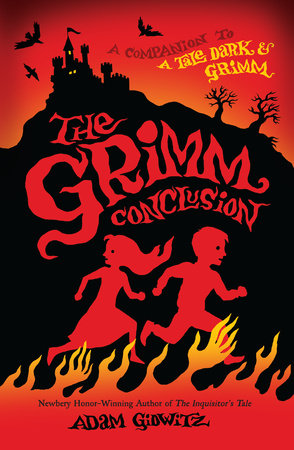

To hear Adam read a selection from one of his books elaborating on the ideas above, click here. Note that the passage comes from a book for older readers and references some more mature events and ideas.