Author-Illustrator Lincoln Peirce on Max & the Midknights and Big Nate

by the Brightly Editors

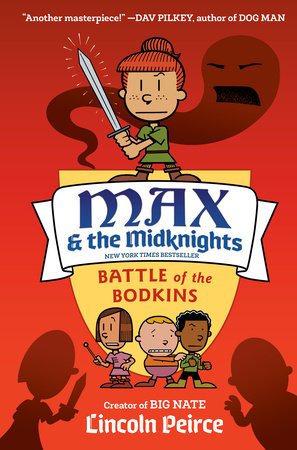

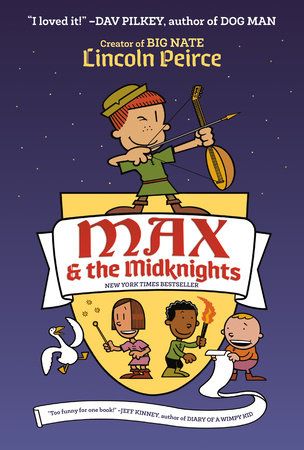

Lincoln Peirce is well-known for the Big Nate series, which began as a comic strip in 1991 and has transformed into a successful book series and an upcoming Nickelodeon television show. Last year, he released a new project: Max & the Midknights; this year, he’s back with the second book in this trilogy: Max & the Midknight: Battle of the Bodkins. Brightly had the pleasure of speaking with Peirce about Max, Nate, the roles gender and identity play in tween novels, and what’s next for these lovable characters.

In the first book in the Max & the Midknights series, Max remained gender neutral until people read the book. Can you tell us why it was important to you to create a heroine and to not tease her gender with the cover art and book description?

That came about as a result of a conversation I’d had a few years earlier with three friends – Jeff Kinney, Dav Pilkey, and Stephan Pastis. We were speaking about the fact that in the children’s book market, all of us had become known for creating stories featuring pre-adolescent boys as protagonists. When we did bookstore events, the kids in attendance were overwhelmingly male. And of course, all four of us are middle-aged men. At a certain point in the conversation, someone posed the question: What if one of us wrote a book with a female protagonist? I thought to myself, “I’d like to try that” – not because I’m particularly interested in the notion that there are “girl books” and “boy books.” I reject that premise. I just thought it would be fun – and a challenge – to subvert readers’ expectations. I knew, based on the fact that I’d written the boy-centric Big Nate books, that just about everyone who picked up a copy of Max & the Midknights would assume Max was a boy. I didn’t want them to focus on Max’s gender, but on her dilemma – she’s living the life of an apprentice troubadour while dreaming of becoming a knight. That’s why I made her name and appearance gender neutral, and why I waited nearly 50 pages to reveal the fact that Max is a girl. I didn’t want to write a book in which her gender is the main issue; I wanted to write a book in which her gender is ultimately irrelevant.

The second book, Max & the Midknights: Battle of the Bodkins, deals a bit more explicitly with questions of identity: Max’s identity as an aspiring knight, first and foremost, but also the idea that people might withhold or disguise their identities for any number of reasons. Max is a kid who’s accustomed to people jumping to conclusions about her identity. That made her the perfect character to drive the story in Battle of the Bodkins. Everyone knows by now that Max is a girl, but that hasn’t necessarily made her path any smoother. And it doesn’t mean that the identities of other characters are always what they appear to be.

What is it about Max that makes her relatable to both tween boys and girls?

It’s fun to read stories about characters whose lives are more eventful than our own, and Max certainly has a pretty interesting life. But a story becomes even more compelling when the characters we’re spending time with are everyday people with identifiable strengths and vulnerabilities. Max has no extraordinary powers – she’s not a superhero or an alien or a kid with magical abilities. In fact, she’s filled with many of the same insecurities as a typical 10-year-old. I’d like to think that, in that sense, she seems authentic to readers. Kids enjoy finding themselves in stories, and even though parts of Max’s life are exotic, it’s easy for young readers to see themselves in her.

At the beginning of Battle of the Bodkins, Max is suffering a crisis of confidence. She wonders if she has what it takes to become a knight, and she compares herself to Sedgewick, one of her Knight School classmates. We’ve all been there! I’m pretty sure that most tweens, whether boys or girls, know what it’s like to feel resentful of a more accomplished peer. Max certainly does, and during Battle of the Bodkins she can be peevish, vain, short-tempered, and snarky. She also has many moments of courage, loyalty, valor, and selflessness. She’s a mixed bag, which I think makes her much more relatable than a character who either succeeds at everything or fails relentlessly.

How do you use illustrations to support the text of a middle grade novel?

I don’t think of illustrations as supporting the text; I see them as part of the text. I use the term hybrid to describe books like mine, because it suggests an equal partnership between words and pictures. Instead of marching alongside one another, the illustrations and text are weaving in and around each other. It’s almost like two musicians working on a duet until it sounds just right. That’s why I would describe myself as a rhythm writer. There’s a definite rhythm that I strive for on each page, but it’s hard to pin down exactly why one piece of dialogue works as part of the text, while another line simply has to be featured in a speech bubble.

Some pieces of editorial insight are cliches, but that doesn’t make them any less true – like “show, not tell.” I think about that one all the time. In Battle of the Bodkins, there’s a lot of action. I could try to write a vivid description of what it’s like for Max to fall into a crater in the Pits of Doom or, earlier in the book, to be swallowed by a giant swamp worm. But it’s far more impactful – and fun for the reader – if I present those events visually. Similarly, moments of humor can become far more memorable if a joke is reinforced by the facial expressions and body language of the characters involved.

I also think it’s important for the style of the illustrations to match the tenor and tone of the text. I consider myself only a fair to middling visual artist, but the clean, simple cartooning style I’ve developed over the years is a good fit for the comedic nature of a book like Battle of the Bodkins. A more realistic or atmospheric approach wouldn’t be as effective.

You’re well-known for the Big Nate series, how are Nate and Max similar? How are they different?

Let’s start with the similarities. They’re about the same age – Max is 10 and Nate is 11. Both are bold and decisive, and both are leaders. They are optimists. Each has a bumbling but lovable father figure; for Nate, it’s his actual dad, and for Max, it’s Uncle Budrick. And they both have certain qualities that make them unique among their peers. In Max’s case, she is skilled in the knightly arts. Nate’s skills apply to a different kind of art – he is an aspiring cartoonist and storyteller. And finally, both characters are clearly good people whose hearts are in the right place. Any difficulties they find themselves in are never the result of their acting out of malice or spite.

But they diverge in many ways. Nate has a much bigger ego than Max and is convinced of his own exceptionality. He’s older than Max is, but not as emotionally mature. He’s impulsive and impatient – character traits that do not serve him well in middle school. Max, on the other hand, has a level of self-awareness that eludes Nate. She is far more responsible; in Battle of the Bodkins, she must make decisions that will impact the safety and security of an entire kingdom. She’s also independent and uncommonly self-reliant for a child of her age – one gets the feeling that Uncle Budrick might fall apart without her. And above all, Max is a protector. She understands that the job of a knight is to shield others from harm, and she embraces this role. Nate is the star of his own life, but his adventures are inevitably low-stakes events. Max, on the other hand, frequently deals with high-stakes, life-or-death conflicts. She is truly heroic.

What’s next for Nate and Max?

I wrote Max & the Midknights as a one-off, but I ended up enjoying the experience so much that I decided to turn it into a series. Book 2, Max & the Midknights: Battle of the Bodkins, will be published on December 1. And I’m already well into writing Book 3, Max & the Midknights: The Tower of Time, which will conclude the series. The story has been optioned by Nickelodeon, and development is underway for an eventual animated TV show and/or movie. I think Max would make a great show. There are countless stories waiting to be told about the residents of the kingdom of Byjovia!

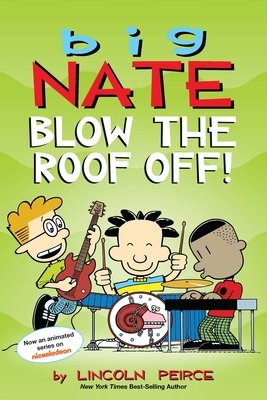

Big Nate continues to appear in newspapers as a daily comic strip; it will celebrate its 30th birthday in January. New comic collections are published twice a year – the next one is called Big Nate: In Your Face. Perhaps the biggest news is that, after many years of false starts and dead ends, a Big Nate animated TV show is coming to Nickelodeon in the summer of 2021. This will help Nate reach a new generation of readers/viewers and might even inspire me to write and illustrate more Big Nate novels. So, there’s a lot to look forward to!

-

Books by the Author:

-

Max and the Midknights

Also available from:

-

About Lincoln Peirce

Lincoln Peirce is a New York Times-bestselling author and cartoonist. His comic strip Big Nate, featuring the adventures of an irrepressible sixth grader, appears in over 400 newspapers worldwide and online at gocomics.com/bignate. In 2010, he began a series of illustrated novels based on the strip, introducing Nate and his cast of classmates and teachers to a new generation of young readers. In the past seven years, twenty million Big Nate books have been sold.

Max and the Midknights, Lincoln’s instant New York Times bestselling novel for Crown Books for Young Readers, originated as a spoof of sword and sorcery tales. He later rewrote the story with a new and memorable protagonist: Max, a ten-year-old apprentice troubadour who dreams of becoming a knight. Max & the Midknights: Battle of the Bodkins returns readers to the kingdom of Byjovia for more high-spirited medieval adventures, supported by hundreds of dynamic illustrations employing the language of comics. Of the lively visual format that has become his trademark, Lincoln says, “I try to write the sorts of books I would have loved reading when I was a kid.”

When he is not writing or drawing, Lincoln enjoys playing ice hockey, doing crossword puzzles, and hosting a weekly radio show devoted to vintage country music. He and his wife, Jessica, have two children and live in Portland, Maine.