Jon Klassen and His Many Hats

by Laura Lambert

When I Want My Hat Back debuted in 2011, The New York Times called it “not just another bear story.” It turned out to be the first of three hat stories, each one with a slightly different tenor, all in Jon Klassen’s instantly recognizable visual style.

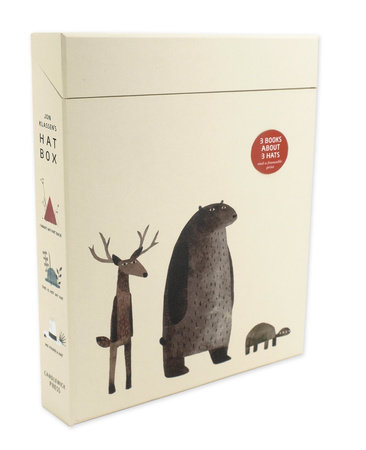

Now, Klassen’s trilogy — I Want My Hat Back, This Is Not My Hat, and We Found a Hat — are available together for the first time, in the appropriately named Jon Klassen’s Hat Box.

Brightly caught up with Klassen to talk about hats and what’s next.

It’s really satisfying to read one after the other because they’re emotionally very different.

They are. They were from very emotionally-different places, I think. They’re really spread out through the years. But they’re also, just in terms of where I was in books, very different.

What do you mean by that?

I think that the first one was born of a lot of nervousness and insecurity and fear about making a book.

Because it was your first?

It was the first book that I ever wrote, and what business do I have making a book? It’s very sarcastic, almost cynical.

Which seems like a risk in children’s books.

It wasn’t so much me trying to take a risk as it was me being scared. When you’re scared of something, you make fun of it. I was making fun of my own capacity to make a book. In I Want My Hat Back, the characters act like they don’t trust me as a storyteller. They’re looking at you, asking, “Is this where we’re supposed to stand? I’m supposed to be, next to the fox?” That’s where I was. I didn’t have the confidence.

So, I got myself off the hook that way — they weren’t actual characters in my story, they were bit players who didn’t believe in the story.

After I read it for a few years on the road, I began to feel a little distant from it, because it felt too sarcastic.

There’s a progression between that book and the third book (We Found a Hat) where I’m trying to be more sincere and trying to create characters that were actually in the story, that felt emotionally in it.

In the second one, This Is Not My Hat, I was already trying to [do that]. The fish in that one is scared. He’s not in a play that he doesn’t know the lines to — he’s really in it. The big fish is in it, too. Everyone’s in it. [The little fish] is still talking to us, but he’s talking to us in a way that you talk to yourself when you are nervous because he genuinely is nervous.

Trying to convince yourself that you’re alright, that you’re okay. It’s a great little voice.

The more I get into this process, I feel like voice is almost all of it. You don’t even have to have a plot if you know what the thing sounds like. There are so many ideas for stories. Plots, you can pull those off the tree forever. It’s the sound of it.

So much so that you can kind of forget the plot while you’re working on it. I remember sending This Is Not My Hat to my editor and the next day realizing, “Oh, I sent you the same book. I Want My Hat Back, it’s the same plot.” But it’s not at all. She said, “No, it’s a different book completely.”

Right, it’s a different emotion. It’s a different character.

But this time, with fish!

And then you have the third book, We Found a Hat, with the turtles. That really is a totally different book. I don’t think it fits with the other two. And that’s what I wanted.

I keep having trilogy ideas just like this… You do one that’s a super strong, graphic idea that feels fresh because you’re new to the world and new to the concept. Then the second one is almost an inverse of that — you take everything aesthetically about the first one and just flip it, so you get these two mirror images of each other, that seem to talk to each other. But then the third one has to be this gradient book that doesn’t really fit with the other two. It’s based on the world that the other two have created, and it wouldn’t exist without them, but it feels subtler somehow.

I hate to put it so simply but… it’s sweet.

It’s a sweet one, and that was the challenge. For me, sweetness wasn’t a premise.

I had other ideas for the third, initially. It had to go one of two ways. One way, I thought, was we had to make one where everyone died — just a battle royale, where we’re left with only the hat because everyone killed each other. As I kept working on it, I felt, I’m not here anymore. I don’t think I want to make this book.

So, then the thinking goes the other way, what if both people in the book like each other, and those are the stakes?

The hardest part was establishing that in a believable way that I could get on board with.

And I’d never done that before. Animals are in conflict naturally. I can rely on your knowledge of that and trust that you know a bear is trouble to a rabbit. But two turtles who like each other, I had to make that up completely from scratch.

That third book was the quieter of the three, in terms of reception, but I’m proudest of it for sure.

Did you have specific people in mind as you developed the bear, or the little fish, or the two turtles?

Not for the first two. For the third one, I think the good turtle is kind of my middle brother, Will. All three books are dedicated to my two brothers, Justin and Will. And I’ve got something about Justin in the works — he’s the strongest of us, probably. But Will, he’s such a good guy. It feels like he’s got these bumpers on him, the way he lives, where he can’t even begin to go out and do something horrible — like what the first turtle was thinking about doing. Once both turtles decide that they aren’t going to take the hat, the good turtle moves on, for real. It’s easy. Or maybe it’s not, but he knows very simply that it’s what has to be done, so he does it. He moves on immediately and says, “Oh, let’s go watch the sunset.” When he’s asked, “What are you thinking about?” he says, “I’m thinking about the sunset.” That, to me … it’s oversimplifying, but it’s Will. My experience with him is that he would be able to focus on a sunset. He has the strength of mind and heart to focus on that.

The book, at least partly for me, is about how you have to try and do that every day. It’s not a decision you make and then it’s done — you have to work at being good. The one hat is going to be there tomorrow, no matter what they’re dreaming about. But they get a break, for that night. I still find the ending sad, but sad in a way I’m proud of. It doesn’t present a solution to the problem, it just gives them a break from it for a while before everything starts up again, and that’s a valid ending.

You’ve answered this question many times before, but I feel I have to ask it — what is it about hats?

Well, I wear hats almost all the time, but that’s not really it.

At the beginning of it, it was a very visual premise. If the bear had an emotional problem that he wanted to solve, like, I’m not happy — you can’t draw that. It’s not a clear problem I can show a kindergartener from across the room.

With all three books, you know they’re over when someone’s wearing a hat. As long as I have that marker, I can go anywhere I want emotionally — even into the weeds a little. I wasn’t going to wander that far off if I had that as my anchor.

Hats are also fun to draw on top of animals. The first one is my favorite hat because it’s almost an abstract shape if someone’s not wearing it.

In one interview, you also said it’s because they’re not necessary.

Right. If the bear wanted his food or money back you would think, “Oh, that’s complicated.” But a hat — all of the emotion and his connection to that hat is that it’s his, and it’s unexplained, and he doesn’t need to explain it.

What are you working on now?

It’s called The Rock from the Sky, and it’s a book with five little stories in it that are interconnected. They are linear, but they skip in time a little bit. It’s sort of about expectation and payoff. The stories have two [main] characters — a turtle and the mole from the first Hat book, and a snake that comes in sometimes. If the first books were plays that were put on in a big production house, then this book is three smaller players who stuck around after everyone went home and found the props.

They’re riffing.

I’m riffing. They’re riffing. I like reading plays a lot. This one has to do with absurdist plays a bit. They all have a little Samuel Beckett in them. The Rock from the Sky, especially, feels like I’m going for it.

I don’t like drawing action, so I have to find ways around it — to give myself permission to not have it. I get much more out of people who are sitting very quietly but who are going through something big, because I can relate to that, and I can draw it. In the Hat books, the characters are morally complicated and the big thing is internal, but in The Rock from the Sky the characters themselves are simpler. They’re still fairly quiet, but the big thing is an actual big falling rock that the audience knows about — but the characters don’t. I can relate to that feeling, too.

-

About Jon Klassen

Jon Klassen is the author-illustrator of I Want My Hat Back, a Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Book; This Is Not My Hat, winner of the Caldecott Medal; and We Found a Hat. He is the illustrator of two Caldecott Honor Books, Sam and Dave Dig a Hole and Extra Yarn, both written by Mac Barnett, as well as House Held Up by Trees, written by Ted Kooser.

Jon Klassen has worked as an illustrator for animated feature films, music videos, and editorial pieces. His animation projects include design work for DreamWorks Animation as well as LAIKA Studios on their feature film Coraline. His other work includes designs for a BBC spot used in the coverage of the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver, which won a BAFTA Award. Originally from Niagara Falls, Ontario, Jon Klassen now lives in Los Angeles.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.