The Importance of Queer Representation in Middle Grade Fiction

by Greg Howard

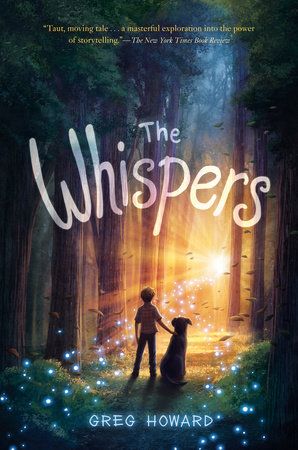

A common thread through my interviews about The Whispers has been the need for better representation of queer kids in middle grade literature. This is not a new idea, just one worthy of repeating. And repeating. And repeating.

The young adult genre is burgeoning with queer representation these days and thank goodness for that. But books for middle grade readers (with a few notable exceptions from authors such as Alex Gino, Tim Federle, and Donna Gephart) are sadly lacking such characters, themes, and stories.

But why is queer representation in middle grade fiction so important?

Growing up as a self-aware gay kid in the rural deep South, I never saw myself represented in books, television, or, movies. Granted that was a few decades ago and things are marginally better now, but we still have a lot of work to do. As a preteen, I was always attracted to the handsome detectives, businessmen, doctors, and lawyers on TV shows. But those handsome men always went home to wives or fell scandalously into the arms of mistresses — never into the arms of other men. Therefore, I was constantly bombarded with the rules and images of a heteronormative society — one in which I knew even from that young age that I did not fit.

In The Whispers, our 11-year-old gay protagonist, Riley, feels lost, isolated, and symbolically erased from his own narrow-minded, religious farming community. He’s never been directly told that there’s something wrong with him because he wants to kiss boys instead of girls, but yet he hides these thoughts and desires, regularly praying for God to heal him of his condition. His only moral frame of reference for his feelings for boys comes from school bullies calling him a fairy and a princess, and from the fire and brimstone sermons of the preacher at his family’s church where he learns that those feelings will get him a one-way ticket to hell. And remember, Riley is eleven.

Riley recalls overhearing a prominent lady of the church — a gossip, as he calls her — saying that it would “kill his mother if she knew he was funny.” And he knew that she meant funny in the way he wanted boys instead of girls, and not funny ha-ha. Like many characters, situations, and family lore in The Whispers, I borrowed this moment from my own life. I overheard this exact declaration from a lady at church one day when I was even younger than Riley, while my mother lay in a hospital bed dying of cancer. When my mother passed a few weeks later, you can’t imagine the guilt and shame I carried around for years, thinking my condition was the cause of her death and that I was responsible.

If there would have been a book or two within my reach that showed a more positive experience for a queer kid my age than what I was living first hand, it very well might have counteracted all the negative comments swirling around in my orbit. A message of tolerance, compassion, and especially hope at that young age probably would have rescued me from some dark moments I barely survived with my life.

That’s why representation matters.

Queer kids need an alternate, positive message to counteract all the negative ones they’re bombarded with on a daily basis. These kids have every right to feel seen, heard, and loved just as much as other kids. If one book like The Whispers can show them that they’re not alone, that they belong, and that they matter, it can make a monumental difference in their lives and possibly even save lives.

But I don’t believe that only queer kids should read middle grade books with LGBTQ representation. Cisgender, heterosexual kids need to read them. Adults, parents, and teachers do too. Because through reading these books, including them in a class library, teaching them as a whole-class text, recommending them to students, children, and other adults, we promote and champion the most world-changing of all superpowers — empathy.

-

Get the Book: