How Writing Helps Me Overcome Parental Anxiety

by Jason Gurley

Late afternoon summer, Texas heat. I’m nine, maybe ten, years old. After spending the day with a friend, I return home to an empty house. My mother — who was there when I left — is nowhere to be found. Her purse is on the countertop. The air conditioning is on. I shout for her, search every room. My worst fear has come true: While I was swapping baseball cards, the Rapture happened. My mom is gone.

Now I’m a few years shy of forty. Soon, my own daughter will be four. And while I spent my childhood fearing cosmic punishment — needlessly, it turns out, as my mother was just on a neighbor’s front porch that day — my daughter won’t. Instead she’s preoccupied with the things she should be blissfully preoccupied with: robot zombie monster princesses and hugs for every imaginary villain she encounters.

Meanwhile, my childhood fears about my own survival have been transformed into anxiety about my daughter’s well-being. My wife hardly worries about Squish — that’s my daughter’s nickname — at all. Her philosophy: If the kiddo trips over her toys and bumps her head, well, she’ll learn from the experience, and probably won’t repeat it. I see irreversible brain damage in every thumped noggin, bone fractures in every tumble. Remember the Calvin & Hobbes strip in which Calvin imagines he’s a human Slinky, tumbling down the stairs? Every single time Squish navigates the staircase to her bedroom, I’m there, cautioning her to pay attention, to watch her step. My nerves are a joke to everyone else. “She’s fine,” my father likes to point out. “When I was her age I was jumping out of trees.”

Since becoming a father, images of children in peril plague me. I’ll probably never read Pet Sematary again. When I see other parents push strollers across the street, the stroller scene from Speed loops in my brain. I have nightmares in which Squish stumbles into precarious situations; in each of them I’m a second too late to prevent the tragedy that follows.

But thank goodness for books.

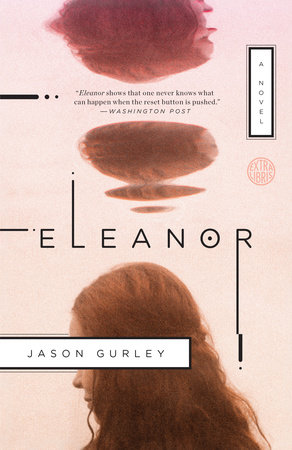

Scores of writers have used their creative outlet as a venue for self-directed therapy. Writing lets you fulfill your deepest, grandest wishes, and it also lets you explore your nightmares safely, clad in a spacesuit, with big, bright helmet lights to illuminate the dark. It comes as no surprise that my work is where I follow my biggest fears to their inevitable, awful conclusions, to see how a person might endure such tragedies. That’s certainly the case with Eleanor, a book that’s about grief and loss and regret and about the restorative power of a child’s love. Here’s the thing about restoration: First you’ve got to break something. And, boy, do things get broken in this book.

Two major tremors in Eleanor set the story in motion. One of these tragic events takes place on the Oregon coast, in a fictional town just a few hours from where I live. That’s far enough removed for me to safely explore it, I think.

But the second event transpires on Highway 26, between my home and my workplace — the most direct route for my daily commute — on a steep, curving stretch of road. There’s a terrible accident in the book, right there in the lane I’ve driven in a thousand times. That one’s a little close to home, quite literally. Each time I’m on that road now, I glance in the rear view mirror, and breathe a little sigh of relief that the backseat is unoccupied, that my daughter isn’t with me. Just in case.

I’m not alone in my predicament, of course. Many people find their sensitivity to tragedy — or even just potential tragedy — jacked up to eleven after becoming moms and dads. And parents sometimes find themselves wanting to protect all the children of the world, even the fictional ones.

I’ve heard it suggested that writing your worst fears can purge that fear entirely. Maybe that’s true. Maybe that’s why the families in my stories endure such trauma, and struggle through to the other side. Maybe writing the worst outcomes helps me to worry a little less about my daughter as she grows up and learns how to navigate the world. Maybe I can’t save my own childhood self from those awful, all-too-real fears, but I can steer my daughter clear of them.

Each night before bed my daughter asks for a story. She usually has a special request or two. “Tell me the story about the time Jessie” — the Toy Story character — “fell into a hole.” In these stories, my daughter is the parental figure, the vigilant rescuer who saves her imaginary friends from dastardly fates. And I, the narrator of these stories, find myself letting go a little more each time I tell them. She doesn’t need me to protect her from everything; she has her own protective abilities. She just needs me to protect her enough.

But I’ll tell you a little secret: I still hold my daughter’s hand on the stairs. And, because there’s no sense tempting the universe, I don’t drive that stretch of Highway 26 unless I must.

Jason Gurley is the author of Eleanor (Crown, January 2016), the fiction collection Deep Breath Hold Tight, and other novels. His stories have appeared in the anthologies Loosed Upon the World and Help Fund My Robot Army!!! He was raised in Alaska and Texas, and now lives and writes in Portland, Oregon. Learn more about Jason and his books at jasongurley.com.