Finding the Space Between Words and Images: Inside an Illustrator’s Process

by Daniel Miyares

When I was four years old I made a very critical observation. I learned that the drawings I made were capable of getting an honest emotional response from other people. From that moment on I knew that drawing was something I could call my own.

Making pictures wasn’t just a path to praise either. It was how I made sense of the world. I could use drawing to make my voice heard or I could use it to disappear and escape reality. This is why at that young age I could say confidently that I was going to be an artist when I grew up. It wasn’t magic or wishful thinking. It was just part of how I learned to do life. Telling stories with pictures was as important to me as speaking. No piece of paper, or wall, was safe in my house.

Thirty-four years later, I’m doing the very same thing … except in the form of picture books. I get to use paintings to bring stories to life. Sometimes I write them and sometimes they’re written by someone else. I try to keep a balance of both. If I’ve written the story, I enjoy the freedom to create both the illustrations and manuscript at the same time. It’s a fluid way of working that sometimes produces really unexpected results for me — and I don’t have to get as much buy-in on the risks I take. The story takes me where it wants to go.

My wife and I have two small children — a daughter who’s nine and a son who’s six. Needless to say when it comes to generating my own story ideas for picture books, I have a deep well of inspiration to pull from. Even still, a lot of my stories seem to come from how I’m navigating my own personal issues. I’ve always told myself that good problems make good stories, so I’m sort of thankful I’m not better at life. I’d have no future in this business if I were.

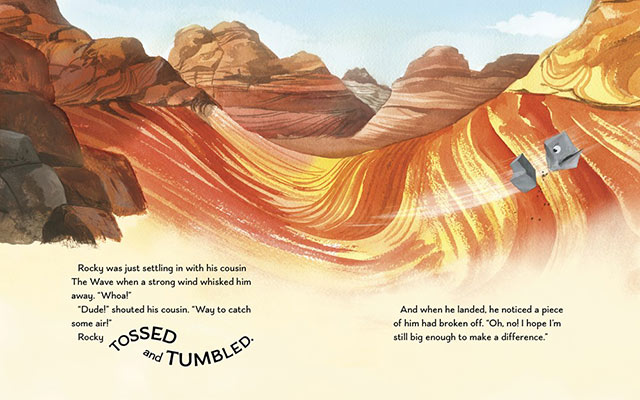

When I illustrate someone else’s manuscript, I look for the stories within the story. My goal is to not only amplify what the author is already expressing in the story, but also look for what isn’t said. Sometimes those unspoken moments or details can be the most meaningful. I try to remember that illustrations can go places it’s difficult for the written word to go, and vice versa.

What I love most though about making picture books is that you have the opportunity to create an incredibly moving and lasting experience for young readers. It’s not because any one word or picture in a book strikes the perfect chord on its own. It’s the sum of its parts that add up to a transformative moment. A great picture book is a well-choreographed dance between words and images with page-turns in between. That space between what the written words are saying and what the pictures are showing is where all the power and wonder are hidden. It’s where the reader (or pre-reader for that matter) is invited to get involved. It’s where they interpret, imagine, and see themselves in the story. Without this breathing room a picture book is simply lifeless.

I have discovered that the quickest way to tell if you’ve achieved this delicate balance is to share your book with a room full of elementary school students. You can see it in their eyes when they make the leaps across those spaces to reach their own conclusions. It’s like they’re piloting the ship at that point and it’s beautiful. Not only because they like your book, but also because you wonder if you might have just set the newest generation of storytellers on their path.

-

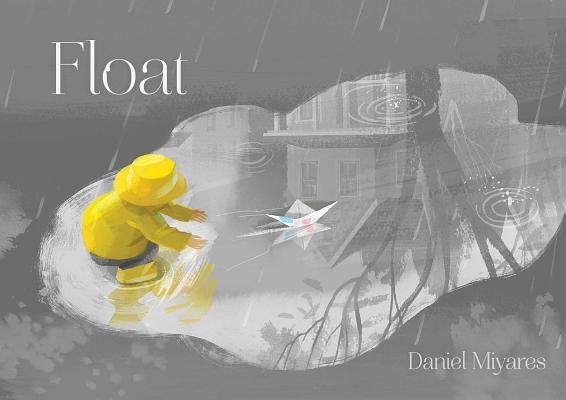

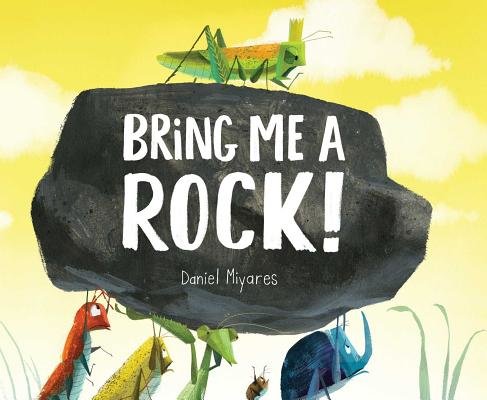

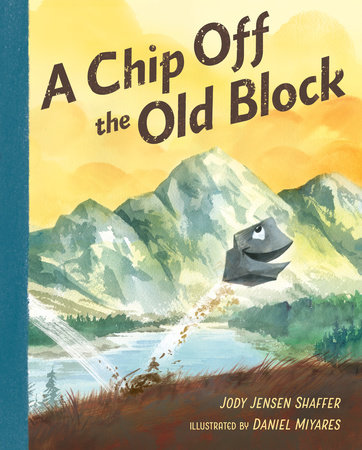

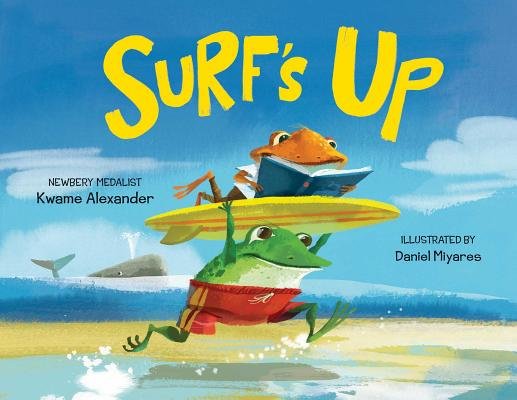

Books by the Author

-

Bring Me a Rock!

Preorder from: