Of all the unusual sweaters I saw during this past holiday season, my very favorite one came from a friend of ours. The colors were pretty typical (your traditional red, green, and white), but what struck me was what it said: “Mama Bear” emblazoned in bold white lettering, next to the image of a very sweet yet protective-looking brown bear. When I asked my friend about the sweater and what it meant to her, she didn’t skip a beat: “It’s me — I’m the mama bear! My job is to protect my little cubs from harm.” She started giggling a bit when she said this, because her “cubs” are actually 10 and 12. But this interaction reflected a major challenge for those of us raising tweens and adolescents.

We’re all mama — or papa — bears to some extent, wanting to protect our little cubs. But is that our entire job description? Probably not! We also want to let our kids learn to roam free and cope on their own, instilling in them confidence and courage to step outside their comfort zones and persevere throughout the ups and downs of life. For example, our tweens may want to prematurely quit the soccer team because they “hate” the coach, drop out of theater because the kids are “so annoying,” or refuse to go to summer sleepaway camp — and as parents, we might have a strong urge to help play the mama or papa bear role and help prevent or relieve their discomfort. But what if their decisions are based in fear? And what’s going to happen when they’re adults, when soccer teams, theater, and camp become jobs and other intimidating adult-like responsibilities that are much harder to simply “quit” or avoid doing in the first place?

We want to build confident, resilient kids who will grow into confident, resilient adults. So how can we thoughtfully nudge our children outside their comfort zones so they can build that confidence and resilience we want for them? Here are some tips that might help:

1. Work to understand why it’s hard in the first place.

Not every case — or child — is the same, so it’s critical to really understand why your child doesn’t feel comfortable trying out something new, such as an extracurricular activity. Do they worry that they’ll look stupid because they’re not good at whatever the activity is? I find that to be an important issue for kids this age. Or perhaps it’s about likeability, and they worry that doing this new thing will make certain people not “like me,” or not think I’m “cool.” Or maybe deep down it’s an issue of authenticity — that they have some narrow sense of their identity and image (say, as an athlete), and this new activity (in the arts) just doesn’t fit this sense of themselves.

Of course, chances are it’s probably a lot of things your child is grappling with. The point, though, is that it’s essential to know. Ask questions. Inquire. Understand what the source of resistance is as a precursor for developing an action plan.

2. Help your child take “just right” steps.

You probably have heard of the idea of a “just right” book — something that’s just the right fit for a child’s current reading level, that’s enough to help them continue building new skills but not too much to overwhelm. The same logic applies to other situations outside their comfort zones. Help your child find “just right” circumstances to take that initial leap into a new activity. Maybe the key is introducing him or her to the theater director the week before to get a sense of the activity and have a friendly face in the crowd on the very first day. Perhaps it’s trying the activity with a friend. Or maybe it’s starting with a one-week sleepaway camp tryout, before committing to the full 3.5- or 7-week summer session. Whatever the case might be, remember you often have the ability to help your child “customize” these initial experiences in small, but meaningful ways … not necessarily to remove the stress entirely, but to make it more tolerable and increase the chances of an early positive experience.

3. Help your child develop a growth mindset.

In her book Mindset, Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck distinguishes between two types of mindsets about learning: a fixed mindset, where mistakes are evidence of your underlying, innate limitations; and a growth mindset, where mistakes instead are an inevitable part of the learning process. As you can imagine, it’s your job as a parent to encourage the latter. This means when your kid says they stink at cross country and want to quit, or that they’re terrible at art and don’t want to continue in the program, it’s your job to provide perspective. Praise their hard work, their effort, their perseverance.

And remember: This same idea applies to you as a parent! Don’t apply a fixed mindset towards the work you’re doing with your children. You aren’t a perfect parent — no one is. Recognize and reward yourself for your effort, your stick-to-it-ness, and your dedication … not for any particular “results.” Those will come, but focusing too much on them isn’t good for anyone.

4. Create forcing mechanisms.

The final tip is to create forcing mechanisms, which are essential for “avoiding avoidance.” Most importantly, forcing mechanisms allow for the possibility for self-discovery. Tell your child that they do need to sing in chorus once at school, but if they don’t like it, they don’t have to do it again. And you know what? They might discover they like it, that they like parts of it, that it’s not as bad they thought, or simply that they were able to stick through the activity, even if it wasn’t perfect — and in some cases, that’s the best lesson of all. I remember going to sleepaway camp myself as a 12-year-old. I was terrified, and refused to get out of the back of the station wagon (yes, it was that long ago!), but my parents didn’t give in. They told me I had to try it once, and if I didn’t like it, I didn’t have to do it again. And you know what? I ended up loving it and staying five years as a camper and three years as a counselor. Going to summer camp was one of the most meaningful parts of my young adult life.

Dedicated parents all want to be mama and papa bears to older kids — and you still can if you shift your sense of what that “bear” is. By providing the structure and support for your child to try new things, and the capacity to build resilience, you’re actually providing them with the most important source of protection they need when venturing into the world.

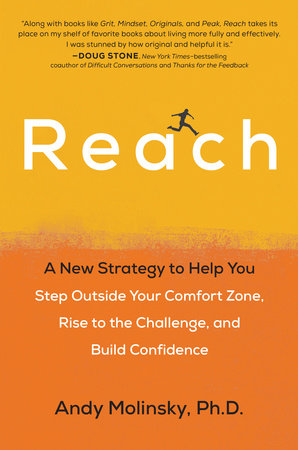

Want more tips for the whole family on building confidence and stepping outside your comfort zone? Check out Andy Molinsky’s book: