“I don’t know if I have the words I need to tell you everything I want to say. I don’t know if I have enough creative impulses to get it all down on paper and truly convince you of my story. I don’t really know where any of this is going. But I remember having dreams once…”

At 22, this was how one of my journal entries turned poem began – with uncertainty and fear. Because at the age of 22, two days before my college graduation, I was diagnosed with scleroderma, a debilitating autoimmune disease with no known cause or cure.

From hospital gown to cap and gown in just 48 hours, my life felt like it was ending before it had even begun. But the idea that one’s life is “over” because of chronic illness or disability is ableist and I would spend the next decade of my life unlearning these beliefs and learning to live with and accept my new day-to-day realities.

Reading and writing poetry has always been a balm to me and when my chronic illness and disability felt overwhelming and scary, poetry helped me in three key ways:

- It helped me process my pain.

- It gave me permission to express my true feelings free from judgment.

- It empowered me and allowed me to regain control of my own narrative.

Poetry To Process Pain

The first question I often get asked when at a doctor’s appointment is “on a scale of 1-10 how much pain are you in?” Then I have to point to a number on a scale with a set of very happy to very disgruntled emojis/faces and answer the question. Sometimes, I get asked to describe the pain, “does it sting, throb, ache?”

When I was first diagnosed it was hard for me to describe the pain I was in and or “how much” I hurt on the scale. But poetry gave me the language I needed to get closer to what I was physically feeling. I began to lean heavily on metaphors and similes to describe my pain and my symptoms when the doctor’s scale didn’t suffice. For example, to describe the inflammation and pain in my joints I might say: “It feels like there is lava bubbling behind my knees and knuckles.”

Metaphors like these allowed me to better describe what my body was going through and it even helped my medical team better understand how to treat me.

Poetry To Empower

Our society often makes people with disabilities feel less than or like a burden. This is one of the many reasons people with disabilities are sometimes hesitant to identify as a person with a disability. And even though it’s taken me many years to learn and embrace it: disability is not a bad word and I don’t have to be ashamed to say that I live with lupus and scleroderma.

Over the years, I have written odes (poems in celebration of) to my crooked joints and swollen hands, haikus about my mouth ulcers turning into flowers, and even angry list poems about how unfairly people with disabilities are often treated.

Writing these poems helped me begin to accept my body and its limitations on my own terms and in my own timeline. In my poems I could mourn for who I once was and begin to celebrate and love who I was becoming. The more ways I found to write about my changing body and my illnesses the more I came to accept them and the easier it became to advocate for my needs.

Poetry Gave Me Permission

One of the long-held and problematic ableist beliefs many individuals still hold is that a chronically ill or disabled person is or must be “strong,” “brave,” or “heroic.” These beliefs and this type of language is everywhere around us and it is hard to escape.

When it felt like the whole world expected me to be brave and strong, poetry gave me the permission to feel what I needed to feel and express it in ways that maybe others weren’t quite ready to hear yet. In my poetry I allowed myself to be afraid, scared, angry and tired.

Using the “I am” and “I am not” list poem format I was able to write about all of the many complex and nuanced feelings I had about my illnesses and disability without the fear of judgment, toxic positivity or platitudes that normally followed when I voiced these feelings aloud. It also helped me break down my own ableist beliefs around these ideas since I too felt that I HAD to be strong and brave.

Living with chronic illness and disability isn’t easy, but it doesn’t mean my life is less than or over with. Poetry helped me understand that because it gave me the language, the power and the permission to process all of my emotions and experiences. And for that I am grateful.

-

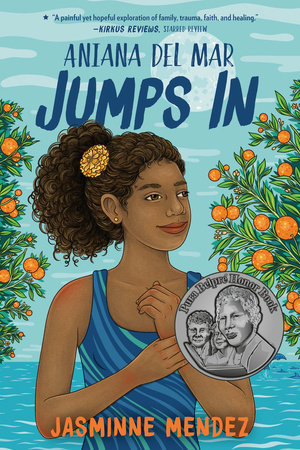

Buy the Book