Ask Your Kids Questions You Don’t Know the Answer To

by Adam Gidwitz

We are constantly asking our kids questions.

Most are practical: “Have you brushed your teeth yet?” “Did you do your homework?”

Some are assessments: “What’s three times three?” “How do you spell because?”

And others are rhetorical: “How many times have I asked you not to kick your brother?!?”

But I have recently embarked on an experiment: I ask kids — hundreds of them at a time — a hard, philosophical question; a question I cannot answer myself.

I’m an author of books for young people, and the idea for this experiment occurred to me during a conversation I had with my editor. She told me that my best books were not the ones that had a message. They were the ones that had a question.

I immediately thought of my novel, The Inquisitor’s Tale, a medieval historical fantasy about a French peasant girl, a young Black monk-in-training, and a Jewish boy. The Inquisitor’s Tale asks the question, “How do we live in a society with people we completely disagree with?” I did not know the answer to that question when I started writing, but by the end, I had settled on a line from a W.H. Auden poem: “You shall love your crooked neighbor / With your crooked heart.”

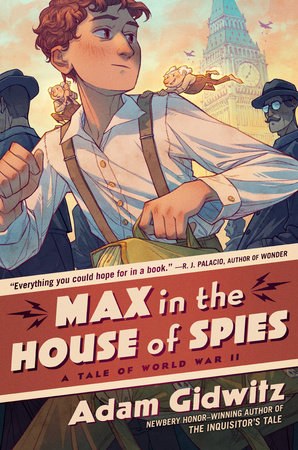

I have a new historical fantasy, Max in the House of Spies, which takes place at the outset of World War II. It’s about a Jewish boy who’s sent away by his parents to escape the Nazis and finds himself living in London with a British spy. While writing the book, I found a quote that beautifully crystallized the questions that motivated the novel: “Between justice and my mother, I choose…”

This is the beginning of a (loose) translation of a statement by Albert Camus. And the tension in it — how do we balance what is right with what is most important to us? — animates just about every character in the book.

Which brings me to my experiment. If my best novels ask a question I can’t answer, why not ask kids? Recently, I’ve visited nearly two dozen schools, speaking to fourth through eighth graders in groups ranging from sixty kids to six hundred. And each time, I pose the question: Between justice and your mother, which would you choose?

Hands shoot up all over the room. The first kid I call on invariably says, “My mom!”

“Why?” I ask.

And they answer with some variation of, “Because she made me!” or “Because if it weren’t for my mom, I wouldn’t exist!”

The next few answers are usually variations on this theme. “My mom, because she cares for me,” or “she feeds me!” In one group, a boy with developmental differences, wearing large, noise-canceling headphones and thick glasses, said, “My mommy cooks for me.” And then he shouted, “Cookies!” The four hundred other middle schoolers gave him a rousing ovation as he beamed.

But soon, the contrarians find their voice. The very first time I led this conversation, it was with a predominantly white group of kids, and when I finally made it around to a Black girl with long braids, she loudly said, “I would choose justice — because that’s what my mom would want me to choose.”

In another group, a boy explained, “My mother is one person, but justice is for the whole world.”

And in an auditorium overflowing with seventh and eighth graders, I asked a boy why he chose justice, and he leaned close to the mic I offered him and growled, “Because I am Batman.” Another ovation.

My favorite argument for justice came from a sixth grader. She made sure she was standing before she said, “I want justice. For everyone. Including my mother.”

And then, at one school, a girl asked me, “What do you think the answer is?”

I replied honestly. “I don’t know. I didn’t ask because I wanted to tell you my answer — I asked because I wanted to hear yours.” And I can only describe the expression on her face as gratitude.

Now, I’ve brought these kinds of questions home. My daughter just turned eight. I continue to ask her assessment questions (“What’s four times four?”) and rhetorical questions (“You still haven’t brushed your teeth!?!?”). But now I’m also asking her questions I don’t know the answers to — about big things, like death, God, and justice.

Her answers give me insight into her world and into mine.

And the questions bring us closer together.

Maybe once we’re good at asking our children questions we don’t know the answers to and listening to what they say, perhaps we’ll learn how to ask other adults the same kinds of questions — even the crooked neighbors with whom we cannot see eye to eye. And when they answer, maybe our children will have taught us how to listen with our crooked hearts.