Sherman Alexie Talks Picture Books, Mirrors in Kids’ Lit, and the

Genius of the ‘Crayon Guy’

by Wesley Salazar

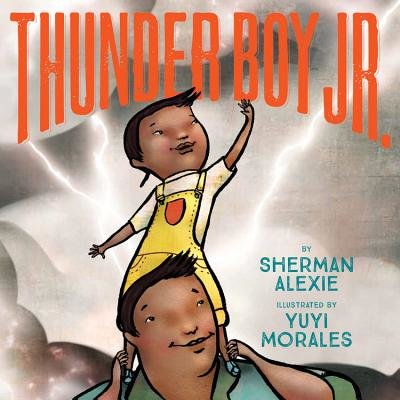

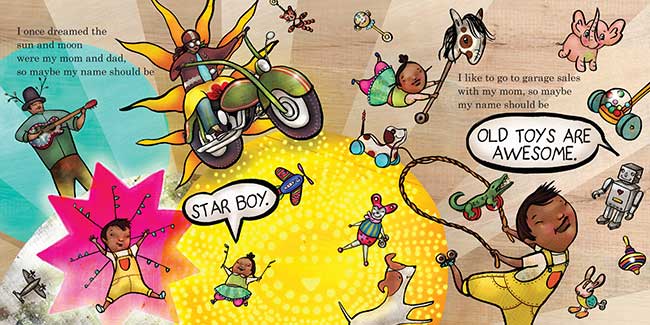

Earlier this year, National Book Award-winning author Sherman Alexie dove headfirst into the world of picture books with Thunder Boy Jr. His captivating new release centers on Thunder Boy Smith Jr., a little boy who’s named after his dad but wants a name of his own. With the help of Yuyi Morales’s striking illustrations, readers are swept into a day in the life of Thunder Boy as he brainstorms new names, like “Full of Wonder” and “Can’t Run Fast While Laughing.” In the end, he does indeed earn his own name — but you’ll have to read the book to learn what it is.

I spoke with Sherman Alexie about his experience writing a picture book, why he thinks Thunder Boy Jr. has resonated so clearly with young readers, and the picture books he’s obsessed with right now. Read on for more!

What inspired you to write a picture book now?

Well, I’ve loved the reactions of teens to True Diary. So I just thought, “Wow, I want to see what I can do for little kids.” So really, it was an artistic challenge that way, but also a big thing is my kids loved picture books so much — you know, where you end up reading their favorites a thousand times — that I wanted to write a picture book that some parent and kid would read together a thousand times. That just seemed fun.

Do you remember which books your kids loved reading over and over again?

Taxi Dog. The Adventures of Taxi Dog was huge for them.

It’s funny how dogs make a few appearances in your books too.

[Laughs.] Yeah, and we never had a dog either until very recently! We’ve only had a dog the last two years, but we didn’t have one when they were growing up — so I think that book was their dog.

How was the storytelling process in picture books different from writing novels for older kids?

Well, it’s the blend of audience, because really you’re writing a picture book probably 70% for the kid and 30% for the adult who’s going to be reading to the kid. You’ve got to write something that’s gonna have sustained interest for both groups.

Did your poetry background come into play at all?

I thought it would because of writing so succinctly, but it didn’t. [Laughs.] I don’t write poetry for kids so it’s a big difference and, the thing is, not having thought of a way something would be illustrated either. I’ve never written for an illustration that way. Even with True Diary, which had an illustrator — that felt more like a graphic novel, which I am familiar with as a reader, the construction of a graphic novel — but picture book illustration, that whole concept was completely foreign to me.

Can you talk a little bit about that process of working with Yuyi Morales?

Well really, what I did was picked. I got done with the text and then said, “Send me all the brown-skinned illustrators.” You know, I wanted a brown person [to illustrate] and they sent me 15 or 20 people’s books. And then as soon as I saw Yuyi’s book Niño Wrestles the World, I knew she was it. She captured boy energy in a way I knew that was perfect. And then we sent her the text and she started working and she sent back pencil sketches and I knew. So I tried to stay out of the way, mostly.

I mean, you hire the illustrator and you let her do her work. She’s the experienced one; I’m the beginner. And then there were just some cultural details we wanted to make clear and she had questions, autobiographical details that she incorporated, but she was telling her own story too. She was adding her own narrative inside the illustrations and so it really is a collaboration.

Did anything else surprise you about writing a picture book?

Not in writing it, but the response — you know, it is so fun to read a picture book to a hundred third graders. I don’t think I’ve had more fun reading to audiences than to the kids this young.

What have their reactions been?

They’re excited about it — especially brown kids. Seeing a brown character in a picture book has been really wonderful for them. A kid raised his hand at a Chicago school, a biracial kid, and I said, “Yes?” and he asked if he could walk up to me. I said, “Yes,” and he walked up and he put his arm next to mine and said, “You and I are the same color.” And I said, “Yes,” and he said, “And I’m the same color as Thunder Boy!” So that’s been really cool.

And then also the evening performances are generally a lot more adults — like 90% adults — but I read to them exactly as I would to third graders. I make them participate, I make them get on stage, I make them jump and dance and sing, so it’s also extra fun to treat adults as if they were third graders. And I think they really enjoy it.

It sounds like it gets lively.

Yes, very much so.

Did you have any mentors growing up — reading-related or otherwise — either personally or just people you admired?

My mentors when I was a kid growing up were my basketball coaches and my speech coaches, debate coaches … I had great English teachers but it wasn’t until college that I started writing. Certainly in high school — my English teacher was Ms. Balum — it was the first place I read Great Gatsby and Jungle, and she really brought the world of literature to me. And it was also the first place I wrote any fiction, was in her class. I sure wish I could find that story I wrote for her; I’ve never been able to find it.

No chance of tracking it down through her?

No, no, this was way before the internet. [Laughs.] That was not on disk.

You’ve touched on this a little bit but can you talk more about what you think it means to kids to see characters that look and feel like them represented in a book like Thunder Boy Jr.?

Well, you feel like you’re part of the world! That you’re seen. And certainly for me, when that happened, when I first read a book about a Native American person and I felt seen — you know, seeing myself inside a book made it easier to see myself inside characters that weren’t Native. Because if I can be a part of one book then maybe I can be a part of all of them.

One overarching theme in your books is people of all ages, but specifically kids, feeling rejected in big ways or just ignored in everyday situations. But Thunder Boy is a little different. Can you talk about that?

Yeah, you know, one of the things when we talk about Native culture we talk about the ways in which we as Native people are oppressed by the dominant culture. But inside of our cultures, we can also be oppressed by each other. There’s just so many cultural, political, social expectations for a kid — a certain way to be an Indian. And I think individuality and rebellion are often as punished inside the Native world as it is in the outside world. So in Thunder Boy, for this rebellious kid to actually be supported by his loving family, it’s very important.

Shifting gears a little bit, how has writing books changed since you became a father?

I didn’t write my first book for a kid until 2007 so my kids were 11 and 6 at that point … I certainly wish I had been writing for them all along!

Has it affected your writing as a whole, outside of kids’ books?

[Laughs.] In many ways I prefer the kids’ book world to the adult book world.

What are some of those ways?

Everybody is nicer in the kids’ book world — everybody, without fail. I think part of it is we have to spend our time with kids … and if you work with kids, you generally have more obvious empathy.

Or hope…

I think really you got it there — there’s just something more hopeful about it. And we all became writers because of the books we read when we were kids. So when I look out in the crowd I think, “Wow, who’s gonna be the writer? Who’s gonna be the writer?”

Can you ever tell?

Sometimes, yeah! There’ve been a few kids … who’ve shown me what they’ve already written and they’re in second grade. “Look what I wrote!” In Chicago there was a kid who showed me his novel, which was four pages and two pictures, and he called it his novel, which is so awesome. And I think he thought it was a novel because it had a cover.

He’ll learn more later…

Yeah, of course I was all happy about it. I didn’t say, “It needs to be at least 120 more pages.” But the sheer joy of reading … the pure love of reading, it’s just ahh. And the pure love of being told a story…

And none of [the kids] raise their hands and ask me about my writing process. [Laughs.] I mean the questions! They ask me questions like, “That book with the blue cover, did you like that one?” You know, “What kind of computer do you have?” Or, “Do you have a dog?”

Rumor has it you were a very voracious reader when you were a child…

Yup!

Do you recall any of the books that you read over and over again?

Well, as in a picture book, it was The Snowy Day, and then there was a picture book called Rifles for Watie — I think it won a Newbery — and it was about the Civil War and a Cherokee gunrunner in the Civil War. I couldn’t even believe there was a Native in a book, a Native who was so big a part of the Civil War, part of something historical.

And then, you know, Carrie, ’Salem’s Lot — the early Stephen King stuff, I devoured.

Suspense and horror…

Oh yeah, a lot of that. And really, with Stephen King, the interesting thing about his work is that his heroes often have impediments, special needs. And I was a special needs kid with speech impediments, so I really identified with that.

It sounds like you encouraged your kids to become readers. How did you keep them reading as they got older?

Well, our house looks like a used bookstore exploded — horizontally when you’re tripping on them!

Well that’s fantastic!

Yeah, exactly. I’m looking at my office right now and it looks like someone lightly neatened the explosion of books — but really, kids do what they see. And they see my wife and I reading all the time. Want your kids to read? You have to read.

After kids have read Thunder Boy Jr. and loved it, what would you recommend they pick up next?

Oh wow, I have not been asked that question! You know who’s really getting me right now picture-books-wise? Oliver [Jeffers] … the Crayon guy! His earlier work. I love the Crayon books — I mean those are his huge hits right now — but I looked at some of his earlier work and it’s so existential. I mean it really is.

I didn’t know him beforehand, but it feels like what I was trying to do with Thunder Boy Jr. and he did it in even a simpler way that I’m really jealous of. There’s one about owning a moose [This Moose Belongs to Me] … And then there’s the penguin one where — I can’t think of the name of it — he finds his penguin. A kid finds a penguin and rows him back to Antarctica…

Yeah! Oh my god, that one made me cry. Just really complex moral dilemmas presented in such beautifully simple ways … Yeah, I’m just obsessed with him right now. And I keep rereading, rereading, by osmosis trying to write one.

And one of the things I’m learning is it’s great to write and to have an illustrator, but I wish I could draw … I mean, I can draw, but not well enough for this and I just have a strong desire. I get illustrating “ideas,” and I’m not going to dictate to an artist, so I’m in that dilemma now where oftentimes I have very strong ideas about illustration. So I’m not really sure what to do with that.

You’re in too deep now.

Yeah, I am, I am. [Laughs.] It’s true! I really plan on writing picture books forever.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

-

By the Author:

A National Book Award-winning author, poet, and filmmaker, Sherman has been named one of Granta’s Best Young American Novelists and has been lauded by The Boston Globe as “an important voice in American literature.” He is one of the most well known and beloved literary writers of his generation, with works such as The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, The Long Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, and Reservation Blues, and has received numerous awards and citations, including the PEN/Malamud Award for Fiction and the Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Award.