How I Learned to Curb My Parental Expectations and Love the Boy I Got

by Ron Fournier

The day I learned our third child would be our first boy, I bought him a tiny baseball glove and got to work on his nursery. A blue and orange blanket with the Detroit Tigers’ Old English “D” covered one wall. Hockey jerseys autographed by Red Wings legends hung from three others.

My wife was just four months pregnant when we named him Tyler and nicknamed him “Tiger” (after a young golfer surnamed Woods) or “Ty” (after a Hall of Fame Tiger called Cobb). I grew up loving sports and loving my own father through sports, so I expected my son to be a jock. It was my great expectation of fatherhood, and my first mistake as a dad.

Turns out, I wasn’t alone in my misplaced expectations. From their first breath — if not sooner — we impose upon our kids huge aspirations. After all, high test scores, championship trophies, lots of friends, and professional success guarantees happiness, right? Actually, no. When a parent’s expectations come from the wrong place and are pressed into service of the wrong goals, kids get hurt. I discovered this late in my job as a father.

Tyler was 12 years old when he was diagnosed with autism. At my wife’s urging, Tyler and I took a series of road trips so that he could practice his social skills and I could bond with him. One thing I discovered on the road was that Tyler feared he would lose my love if he stopped playing sports — I was dismayed.

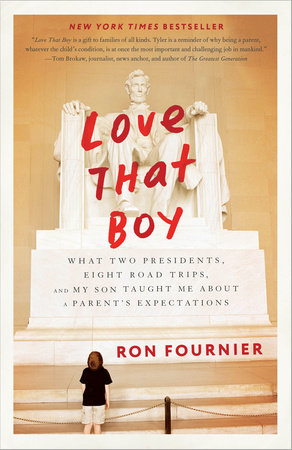

In my conversations with other parents while researching Love That Boy: What Two Presidents, Eight Road Trips, and My Son Taught Me About a Parent’s Expectations, a book about the causes and costs of parental pressures, I focused on two themes: the things parents want in their kids, and what their children actually need.

Here are five common expectations about raising children that I frequently heard from parents, things many of us think we want for our kids, and the realities of each:

Expectation #1: For our kids to be “normal.”

The most primal of parental expectations is the desire to see your child accepted and avoid hearing them described with the dastardly a-words: atypical and its caustic cousin abnormal. My wife Lori had an endearing way of expressing this desire. “All I want,” she said during each of her three pregnancies, “is a baby with 10 fingers and 10 toes.”

The reality: The fact is none of our children are normal. What makes them different is what makes them special.

Expectation #2: For our kids to be intellectual.

Of all the Google searches starting “Is my two-year-old …,” the most common next word is “gifted,” according to Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, a writer and economist who studied aggregate data from Google searches. “It’s hardly surprising,” he wrote in the New York Times, “that parents of young children are often excited at the thought that their children may be gifted.”

The reality: Two-year-olds aren’t supposed to be intellectual. Average is good enough. The next parent who Googles “Is my two-year-old gifted?” should get a curt response: “Your two-year-old is a gift.”

Expectation #3: For our kids to be popular.

For decades, magazines, books, and self-appointed leaders of the expert industrial complex pounded into mothers and fathers a message freighted with pressure: Popularity is good for your kids and it’s your job to help make them cool. The subtext: You’re only as successful as your child is popular.

The reality: Popularity is a trap. Research shows that teens who act older than their age by engaging in risky behavior are considered by their peers to be popular. These “cool kids” had a 45% greater rate of problems due to substance abuse by age 22, according to a University of Virginia study, and a 22% greater rate of criminal behavior, compared with the average teen.

Expectation #4: For our kids to be exceptional.

Parents encourage, guide, nudge, push, and force their kids into all forms of organized activities — sports included, of course. But there’s a broad bouquet of parenting expectations too, such as preparing for and attending science fairs, spelling bees, singing contests, class elections, beauty pageants, bake-offs, ballet, and more. We want our children to be stars, the most valuable something. We love our kids and want the best for them, so why not help them be the best?

The reality: Because this pressure leads to pain (every 25 seconds in America, a child visits an emergency room for a sports-related injury), mental illness (one in every five 18-year-olds has suffered major depression), and a warped sense of values (one in every 10 kids admits to cheating in a competition).

Expectation #5: For our kids to be happy.

My conversations with parents for my book almost always started with this question: “What expectations do you have for your children as they grow up?” Most replied along these lines: “All I want is for them to be happy.” But I wonder, is that really all they want? After all, I’m sure there are some happy serial killers.

The reality: Most parents confuse happiness with pleasure. True happiness is the result of doing hard but good things over and over. People who live with a sense of purpose are more likely to remain healthy and intellectually sound, and even to live longer than people who focus on achieving “happiness” via pleasure.

What do our kids really need? A parent’s empathy and acceptance, for starters, along with the grit and resilience that comes with failure. I didn’t right-size my expectations for Tyler until after our road trips together, where I learned to view my son through the generous eyes of others, and to be proud of what I saw.

I learned to accept Tyler for who he is, not what I want him to be.

I learned to guide, not push — a blurred line all parents must walk. There is a world of difference between dancing in the living room with your daughter and forcing her to take ballet classes. The first approach is a playful and authentic way to expose her to a potential hobby. The second is conflating your aspirations with hers.

You have two choices as a parent: You can shape and misshape the child of your dreams, or love the one you got.

No, Tyler is not my idealized son. He is my ideal one.