10 Myths About Middle School-Aged Kids

by Judith Warner

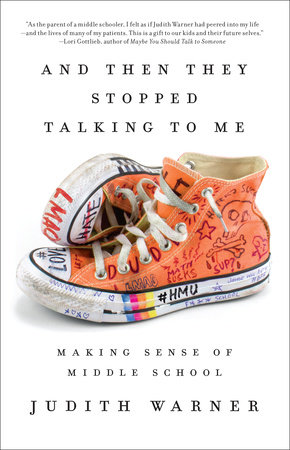

Middle school is a topic that just about everyone has strong feelings about. When I started researching for my book, And Then They Stopped Talking to Me, I knew I had to keep an open mind. Conversations I’d had later in life with my former friends from sixth, seventh, and eighth grade had shown me that my memories of what I’d done and what had been done to me – and, most embarrassingly, how nice a person I’d been – weren’t 100% accurate. I also found that my daughters and their classmates didn’t conform to most of my expectations about what middle schoolers are like today. The more years I spent as a middle school parent, the more I started to wonder how much of what we think we know middle school-aged kids is really about them – the dramas, challenges, and changes of early adolescence – and how much is, in fact, about us and our difficulties in navigating a new phase of life with our tweens and young teens.

The following list of 10 “myths” of middle school looks at the kinds of assumptions I had to question, and also provides some of the fascinating truths I found.

- “Oh my god – raging hormones!”

It’s not even a full sentence. It can’t be – because generally, whoever is speaking gets overcome with emotion mid-way through and ends up sort of scurrying away. Middle school – which often encompasses puberty – is a time of life that’s really tough… and not just for kids. The children in your life go from being adorable, cuddly elementary schoolers to foreign creatures with cast-down eyes constantly glued to their phones. Psychologically, the kids are often super-glued to their friends, and those friends are infinitely superior to their annoying, judgmental parents. Adults’ feelings around their children’s attachment to their friends and resentment of their parents are complicated: there’s bemusement, sometimes admiration, a lot of annoyance, some anger, and even grief. That’s why it’s easier to grab onto the low-hanging fruit and chalk it all up to the changes of puberty.

The problem with this explanation is that at puberty, hormones don’t “rage.” Estrogen and progesterone do begin to fluctuate in girls as they start their periods. Boys’ testosterone levels do rise – as much as thirty times – between the beginning and the end of adolescence. But adolescents don’t have higher levels of sex hormones circulating in their bloodstream than young adults do – they just react to them differently. And, aside from making kids more emotional, they’re not directly or even chiefly responsible for a lot of the unlovely things we associate with the middle school time of life: the moodiness (which actually gets worse a couple of years later), the difficult behavior with parents, the cliquiness, meanness, and flirting — however expressed. All those things are far more affected by the kind of environment we live in and the kind of messages middle schoolers get from their families and at school – and by the mismatch between what middle schoolers need and what they’re offered.

- It’s a waste of time trying to teach them anything.

Educators who don’t like working with middle school-aged kids, but are forced to work with them, have said this for as long as middle schools have existed, which isn’t really all that long a time. The first junior high schools came into being in 1909, and it wasn’t until the Great Depression that most American kids stayed in school through their early teens. From the start, even experts who were excited by the prospect of creating classrooms tailor-made for their “peculiarities of disposition,” as one reformer delicately put it, argued strongly that if the schools were to succeed, they’d have to be vigilant about catching and controlling their students’ baser instincts. (“The opportunity for good is only equaled by the possibility of evil,” wrote another.)

None of that was lost on the students, who very early on made clear that they would return adults’ dislike of them in kind. It didn’t take long before the schools were considered a failure. The kids were bored and alienated, their teachers uninspired. Worse still, the adults charged with their education tended to blame the students if they didn’t succeed, if school was a misery, if – even after the junior high schools were phased out and the ostensibly more child-centered middle schools replaced them – everything essentially stayed the same. It was convenient, once again, to blame “raging hormones”: the idea that kids of junior high or middle school age were far too bound up in one another to ever spare a thought for what they were supposed to be learning. But that idea, once again, reflected more on adult prejudice than it did on kid potential. Once again, it was very partial and skewed, over-focused on the externals of puberty, and ignorant of the equally important and life-changing events happening inside kids’ brains. The fact is: Estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone change the brain in a number of ways that have huge implications for kids’ abilities to think, create, and learn. They make kids more attentive and attuned to the world around them. Kids become capable of higher-level reasoning and reflection, can think abstractly, and can even be self-aware and self-reflective. Their memory is better than it’s ever been and will ever be again. All of which mean they can learn and do far more complicated, sophisticated, and interesting things in school – if they’re given the material to work with.

- All they want to do is be on their phones.

Not all the time. Not when they have something else that’s worth doing. They do want to be connected with their friends, more than at any other point in their lives. Puberty sets into motion all sorts of brain changes that make kids care more than ever before about how other people see them, and crave approval, attention, and admiration from their peers in particular. As one researcher says, they’re “virtually addicted to popularity.” At the same time, though, if their newly amped-up, tuned-up brains are given something worthwhile to do, middle schoolers will go at it with alacrity. They’ll throw themselves into group activities, and some even find joy in getting lost in projects alone. I’ve visited middle school afterschool programs – particularly in low-income communities — where kids jump at all that’s on offer, from learning new sports to how to cook. I saw my own daughters come into their own as artists and musicians during those years. And I recently discovered, when I found some old papers in my mother’s apartment, that it was in middle school that I first started seriously wanting to be a writer. It was then that I decided I wanted to become fluent in French and even live one day in France. All the things, in fact, that would ultimately make me who I am as an adult were already present in eighth grade.

- They hate their parents.

It sure feels that way sometimes. They see everything that’s wrong with you, from your belly fat to your hypocrisy. And they’re glad to share their new findings. It’s awful, when the child who begged for your attention just a year earlier shuts her bedroom door in your face. But it’s also developmentally appropriate. The truth is, our kids are programmed to separate from us, and us from them. But our timing’s all wrong, and for modern kids and parents, it’s in middle school when things are particularly out of whack. Kids need to pull away, to become themselves in the larger world at precisely the point when parents want to hold them close and protect them. They’re unbalanced and uncertain and need our strength and steadiness just at the time when we ourselves, very often, are becoming a little unhinged by the struggles and stresses of early middle age. They’re arguably at their worst, and we’re not at our best.

All of which can create a highly combustible situation. And yet, not one that’s necessarily pathological or even all that problematic. Interestingly, when researchers have asked middle school-aged kids how they feel about their parents, their responses have tended to be generally pretty good. And when psychologists have turned an objective eye to what’s going on in our homes – coming in to observe, rate, and quantify all those blow-ups that seem so big and so fray our nerves — they tend to find it’s not very serious. There’s a lot of bickering, for sure (especially between mothers and daughters), but the discord doesn’t really cut very deep. That is to say: it’s surface-level stuff, the back-and-forth of negotiating closeness and distance, belonging and independence. You can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs, and your ability to enjoy and feel gratified by parenthood is likely to at least sometimes be what ends up getting scrambled during this all-important life transition. But your relationship with your kids won’t be broken. And neither will you.

- The popular kids are horrible people.

They certainly seem to be, especially if your kid was once “in” and is now, suddenly, “out.” Or if they are ignored, treated like they don’t even exist. Worse still is if your kid is being ridiculed or all-out bullied. But, once again, the facts tell a much more complicated story. Experts talk about two kinds of popularity: the kind where people really like you and the kind where you have power and high status. Middle school popularity tends to be of the second kind. How one achieves this level of popularity has stayed remarkably the same over time: being good looking, having money (relative to peers), being on the older or more mature end of your peer group, being athletic, and – most interestingly – having a specific set of social skills that allow you to read people well, connect to them easily, and go with the flow. Another way of seeing it is that middle school’s popular kids tend to be the ones who have won the lottery when it comes to successfully getting through a phase of life that’s all about leaving the warm bubble of home to find a new group among their equally adrift peers. So “popularity” isn’t a magical quality – and it isn’t necessarily a moral failing, either – it’s the outgrowth of a set of characteristics, some inborn and some learned.

Being a winner at the game of middle school popularity, however, isn’t without its downsides. What I found, interviewing former popular kids about what they’d been like in middle school, was that when they looked back on the experience, they said that they’d been scared. That they did the mean things they did because they knew that their status was wobbly, that “popular,” when it’s of the middle school type, is a very insecure place to be, because the alliances are ever-shifting, and being at the top of the social pyramid requires many more people to be down below. These people also noted that the very same skills that got them to the top in middle school came with a liability: they could never turn them off. And as they got older, they could never stop thinking about their status and other people’s status, who was up and who was down, who was in or who was at risk of getting pushed out. They were (and often still are) hyper-aware of the power dynamics in every room, and though in adulthood, the ones I spoke with said they tried very hard to tune all of that out, to deny their “mean” impulses, and to steer themselves away from other people who, their social radar told them, were wired just like them — they couldn’t really escape.

- Mean kids grow up to be mean adults.

I assumed this was true as well, before I started hearing people’s stories. In some cases, there was some truth to this — their social instincts to keep control still existed. But the opposite was true as well: I spoke with a striking number of adults who felt, in a certain sense, cursed – haunted by the memories of what they’d done to others, burdened by their acute powers of social observation, and, above all, fearful that their kids would either turn out to be just like them in middle school or – admittedly worse – end up as victims of mean kids. That awareness, of how they themselves might have treated a son or daughter they so deeply adored, was simply torture. There were people who essentially spent the rest of their lives trying to make up for the harm they’d done in middle school.

- The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Yes and no. This myth fascinates me. There’s research to show that some of the traits that make kids popular or unpopular in middle school are inherited (at least up to a point): introversion or extroversion, for example, or the kinds of mental health challenges – anxiety, mood disorders, ADHD – that can contribute to a child having a hard time fitting in and being accepted by other kids. Family social style definitely plays a role, too: social skills, after all, can be learned and reinforced, just like skills for math or reading, and kids definitely take in what they see modeled for them day after day. Anecdotally, it always seemed to me that, no matter how much kids (especially daughters) were pushing back against parents at home, they still, in style and self-presentation, hewed pretty closely in middle school to the standards set by their parents – it was really in high school and college that they’d start to go their own way. And yet, teachers and school administrators I spoke with also drew on their (much wider) anecdotal experience to note that, especially when it comes to bad behavior, the apple often did fall far from the tree, especially in middle school, because middle schoolers are trying to self-differentiate, and sometimes do so by making very bad choices. “This is a time when you sometimes see a kid really turn on a parent’s values because that’s a great way to break away,” one longtime school principal told me. “Sometimes the nicest parent comes in with the most defiant child. You really feel for that parent. ‘I thought I raised this nice kid,’ they say, and I say that the nice kid is still there, just very well-defended at this point.” In fact, she added, “It may be that the parent is too close to the child … and this is the only way the child can get away.”

- You’re lucky if you have a late bloomer.

There’s a lot of research on the problems that going through puberty early causes kids, especially girls, although boys suffer when they’re hit early with adults’ preconceptions and expectations, too. But it’s also very hard to go through puberty late. It may be easier in some ways on parents – you get a rain check on the pushback and bickering – but for kids, the delay sets them apart and, sometimes, back. That’s because going through puberty later doesn’t just effect kids’ physical appearance; some of the new cognitive capabilities typical of middle schoolers will end up coming later, too. As a result, otherwise very smart kids may struggle with school assignments and organization, especially if they’re in schools that make what were formerly high school-level demands on their middle school students. They may be out of step socially with peers who are entering new phases in their relationships, not just romantically, but in terms of the sophistication of their social interactions and maneuvering.

If you have a kid who’s on the young end of normal, it’s likely to be hard. But there are things you can do to help: First, remember that there’s huge variability in early adolescence in what’s still considered in the range of “normal” – don’t pathologize, and try to keep your middle schooler from doing it, too. Be confident that they’ll catch up, and just remember that, regardless of how other kids are treating them, they’re probably giving themselves a hard time. No one likes to be different in childhood – and middle school is the time of life when being just like everyone else matters most of all.

- You won’t believe what they’re getting up to.

Yes, you would – because you got up to the same things. You just did them in different ways, using very different technology. They have “sexting” (verbal sexting, I mean – sending nude or nearly nude images is very rare in this age group), we had dirty notes passed in class. We had gross-out hang-up calls. Nasty, whispered propositions spread from the back of the bus to the front. Friends were “ghosted” in the past – it just happened in real life, not online. Anonymous insults, embarrassing disclosures, boasts (and lies) about sexual exploits happened inside “slam books,” rather than on Yolo. In fact, if you’re apart of Gen X, or an older Millennial, there’s evidence to suggest that middle schoolers today are getting up to a whole lot less – in terms of sex, drugs, smoking, and drinking – than you (or others your age) did.

It’s hard to believe this, because for so many decades we’ve been fed a steady diet of scare stories about all the shocking things that middle schoolers do. (Rainbow parties! The Slenderman Stabbing!) But much of that reporting came from the first wave of Baby Boomers, who did, arguably, grow up in a safer and easier time (if they were white and middle class, at least), and in early middle age turned their own angst and sense of loss at their children’s early adolescent passage into a cultural psychosis. Multiple surveys proclaim the same truth: middle school for this generation is more protected, more innocent, and – dare I say it – in some ways, at least in some communities, nicer than it was when we were growing up.

- Social media is ruining our kids.

This myth is based on fear of the unknown. Social media is just a newer medium of communication. It’s a tool, and like all tools, it can be used safely and helpfully, or it can be used dangerously and harmfully. There has been a lot of discussion about middle schoolers’ social media use in the context of very real rising rates of anxiety and depression today, but the science behind the notion that there’s a causal relationship between them is very weak. More nuanced reporting shows that, like so many things, social media meets kids where they are: those who are insecure become more so, those prone to anxiety or depression can be made worse by it (though some benefit from the added opportunities for connection!); those who have problems with self-regulation may gorge on it to the exclusion of nearly everything else.

In school, we teach media literacy — how to identify valid research sources, how to separate fact from opinion. We ought to provide lessons in social media literacy as well. Get kids thinking about the psychology that lies behind creating a curated life online. Deconstruct FOMO, get them to question what their social media presence does or doesn’t do for them, and help them step outside themselves so they can try to understand how their words (and images) affect others. Vilifying social media isn’t going to help us help kids. Neither is trying to monitor all their online activity; it’ll just make us crazy, and they’ll only find new and ever more secretive ways to evade us. But if we can educate them to think critically, we may be able to break its spell.

-

By the Author