Confidence Over Competence: Empowering Girls to Love Math

by Jennifer Swender

When I was in fifth grade, I was a milk-seller. Chocolate 6¢. Regular 5¢. Skim 4¢. This was a coveted class job. I don’t remember the exact details of the hiring process, but I do remember the two reasons I was chosen:

- I was good at math. (The complicated pricing structure made for some tricky change-making.)

- They needed a girl. (The heretofore milk-sellers were all boys.)

I also remember the subtle subtext — a “math girl” can be hard to find.

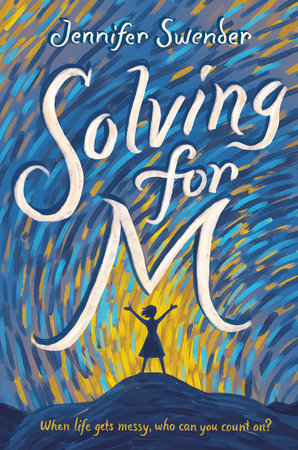

In Solving For M, fifth-grader Mika doesn’t consider herself a math girl at the start. “I’m more of an art person,” she says. “Numbers are numbers. I don’t know what there is to get so excited about.” But unlike Mika, I can remember rushing with a group of middle schoolers from lunch back to math to pick up our newly graded tests. It wasn’t some kind of overachievement competition — it was algebra. It was fun! Picking up those tests was like turning to the answer key of a crossword puzzle to see how many you’d solved.

But I have another kind of middle school math memory. One marking period, we had to grade ourselves for the entire quarter. I don’t recall the exact details of the conversation, but I do remember the two reasons I gave myself an A:

- I always got an A in math.

- The lowest grade I’d gotten was an 85%.

The teacher informed me, however, that I was getting a B due to that selfsame 85% — or maybe it was an 82%? (Cue the self-doubt.) I don’t remember the exact words, but the message received was clear: a group of us had apparently gotten “too cocky.”

I heard this criticism not as a challenge (I’ll show them next time!) but as chastisement. I’d had the audacity to overestimate my performance. Heaven forbid we allow middle-school girls to get overconfident. Especially in math.

According to a study by Florida State University researchers, “When it comes to mathematics, girls rate their abilities markedly lower than boys, even when there is no observable difference between the two.” So, a major contributing factor to the “math gap” between girls and boys may be confidence rather than competence. Or perhaps it’s the conditioning of how expressions of confidence are perceived. In her article “Why the Confidence Gap is a Myth,” Stéphanie Thomson argues that “women are hesitant to talk up their accomplishments” not because of some innate lack of confidence but because “they are often penalized when they do.” As the authors of the Florida State study note, “boys are encouraged from a young age to pursue challenges … while girls tend to pursue perfection, judging themselves and being judged by more restrictive standards reinforced by media and society at large.”

In Solving For M, the quirky math teacher, Mr. Vann, doesn’t place much value on perfection. He teaches the chapters of the textbook out of order and reminds his students that “life is mostly estimation.” Within the carefully orchestrated classroom chaos, he gives his students multiple ways to be right, multiple ways to be smart, multiple ways to be a “math person.” He has them draw, build, write, run, roleplay, debate, design, cook, rhyme. He has them apply what they’re learning to “real life” and doggedly insists that they explain their thinking. After some time in this unorthodox petri dish of mathematical thinking, Mika notes, “I never thought of myself as one of the super-smart kids before, especially not in math. But this year, I feel like I kind of am.”

Once, an astute young reader asked me why — in a book full of strong girls and strong women — why wasn’t Mr. Vann … Ms. Vann? The question took me aback. The truth is, it never even occurred to me. In my imagination, Mr. Vann was always a man, probably because most of my own math teachers were. (Cue my high school trigonometry teacher reminding us, in true Mr. Vann fashion, that “fools rush in where angels fear to tread” and to “never, ever touch your asymptotes.”)

But I trust that Mika and her friends, Chelsea and Dee Dee, will encounter multiple math role models of all genders in their world, and that they themselves will grow up to be those role models for others. As one of Dee Dee’s T-shirts says: This is what a scientist looks like.

Several years ago, I had the opportunity to observe a kindergarten math lesson. The teacher placed seven counting bears in a line and posed the following question: if you counted the bears starting from one end of the line, would you get the same number if you started counting from the other end? One girl raised her hand.

“Not always,” she said confidently.

I smiled. Obviously, seven bears is seven bears is seven bears, whether you count them left, right, or sideways. But this wise educator didn’t respond with correction or clarification. She took a moment and said, “Please explain your thinking.”

And the student logically did just that.

“Sometimes,” she said, “people count wrong.”