Subverting Enchantment

by Emily Winfield Martin

The reason we love retelling fairy tales is simple: they are our common language. Far deeper than the English words “Once upon a time,” is the Language of Icons, the universal symbolic vocabulary of the stories: the Maiden, the Monster, the Babe in the Woods. Those things, in their visceral simplicity, have real enduring power.

Once you’ve started on this path, there is a choice. For why wield the power of the Icons unless you wish to subvert them, but then … how? Will you take these things and make them funnier, scarier, more emotionally true? Will you use old stories to talk about something profoundly new? Will you make the Huntsman weak and the maiden strong? The witch kind and the monster gentle?

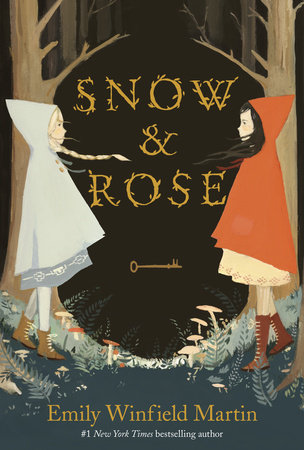

As I wrote my own retelling (Snow & Rose, which has just published) I thought a lot about these choices, just doing the dishes and walking around the house. And I became especially interested in two very general types of retelling. For brevity’s sake, I’ll call them the Winking and the Sincere.

Neither one is right or good, neither is better than the other. And most stories obviously have elements both Winking AND Sincere. But the choice is important, for like many bargains found within a fairy tale, for everything you gain, there is something you give up.

Let’s begin with the Winking story. The strength of this type of retelling is that it plays to the universal nature of the Icons, to the intrinsic delight in our recognition of the archetypes and our familiarity with them. This treatment is typically irreverent, often funny, and never precious, precisely because it seeks to use our preexisting ideas of the Icons as a way of quick establishment. It might be confirming what you’d expect: “Look at the spoiled prince!” and we will nod knowingly. Or it might be written to subvert your expectations: “Look at the spoiled prince! But wait! He is bringing bread to the peasants.” The Winking story is special for children, perhaps more so than for any other kind of reader, because of their newness to the great joy of Knowing, of being part of an inside joke.

Something like “Shrek,” even though it’s a hodgepodge of fairy tale characters and Icons and not a retelling of one single story, is quintessentially Winking. It’s funny, and silly, and sweet, and that is what it seeks to be. But I think it also highlights the intrinsic drawback in the Winking story, the thing you give up.

The Winking story’s fate is the same as the Horror Comedy. It works because of our familiarity with the Icons and tropes (the final girl, the cabin in the woods). But the very thing that makes it work, the nods of recognition, the inside joke of it all, is also the thing that bars the story from the cathartic realms of the stories to which it pays knowing homage … because Horror Comedies cannot truly be scary, not in the same way.

In a Winking story, the defeat of the monster, the well-earned happy ending, it cannot break your heart, not really. There is a certain remove, a distance. Because the purely Winking story is a little bit jaded.

On the way to Sincere is a strange set of short stories that make up one of my favorite books of all time. The Bloody Chamber (decidedly not for children) is Angela Carter’s book of retellings, comprised mainly of Perrault’s fairy tales. In these stories, the notions of the hero and the monster are subverted with a ‘70s feminist flourish, in the form of a liberated Bluebeard’s wife and several surprising (even shocking) variations on Beauty and the Beast and Red Riding Hood. I would say the beating heart of the stories, the earthiness of them, the naked longing within them edge them into the Sincere column, although Carter is surely both Winking and Sincere.

Then we arrive at a purely Sincere story, my story*. Snow & Rose is this way because that is what a story of loss and grieving, of trust and belief, needed to be. It was important to me that the Icons: the Beast, the Bandits, the Brave Maidens, the Woods itself, retain their original symbolic heft, while I was also free to embroider onto them, with threads of interior lives, and hope, and extra bits of magic. I could use the elements of the Grimm’s tale to talk about poverty, and wealth, and nature, and death.

The Sincere story, especially, seeks the fundamental truths of the human experience (love, sorrow, wishes, greed, cruelty) within the original tale. Its chief concern isn’t reference to our common canon of stories, but the illumination of our common, eternal selves. The heart of this kind of story, the gut-level humanity of it, is unobstructed and catharsis can be deeply earned and felt.

The drawback, of course, the thing you give up, is that this kind of story is no doubt too expected, too heartfelt for some modern readers. It is 2017, and we know this story. If you are not going to do a clever thing with that Knowing, or if the reader is hoping for a Winking story, the Sincere story is altogether too straightforward, perhaps precious. The Sincere story is, well, sincere.

As often happens in fairy tales, in our own world, the weakness of one is the strength of the other. When we subvert enchantment, the most important choice, the only choice, is how.

* It is admittedly the tiniest bit Winking in its exploration of the idea of storytelling itself, of the symbols and their significance.